Diagnosing and Classifying Vertebral Compression Fractures: Understanding the Silent Threat of Osteoporosis

Vertebral compression fractures (VCFs) are a common and often painful consequence of weakened bones, particularly in individuals with osteoporosis. These fractures occur when a vertebra in the spine collapses or cracks, leading to back pain, reduced mobility, and potential deformity. Early diagnosis and proper classification are critical for effective treatment and preventing further complications. In this blog post, we’ll explore what vertebral compression fractures are, their symptoms, causes, diagnostic process, and how they are classified, all explained clearly for a general audience.

What Are Vertebral Compression Fractures?

Vertebral compression fractures occur when one or more vertebrae in the spine—typically in the thoracic (mid-back, T1-T12) or lumbar (lower back, L1-L5) regions—collapse or fracture due to weakened bone structure. These fractures are often linked to osteoporosis, a condition that reduces bone mineral density (BMD), making bones brittle and prone to breaking under minimal stress. Unlike traumatic fractures from high-impact injuries, VCFs can occur during everyday activities like bending, lifting, or even coughing.

VCFs are a significant health concern, affecting about 20-30% of osteoporosis patients and contributing to 700,000 fractures annually in the U.S., per a 2020 study in Osteoporosis International. They can lead to chronic pain, spinal deformity (e.g., kyphosis), and reduced quality of life if not addressed.

Causes of Vertebral Compression Fractures

VCFs are primarily caused by weakened bones facing normal or minimal stress. Key causes include:

- Osteoporosis: The leading cause, where low BMD makes vertebrae fragile, especially in postmenopausal women due to estrogen decline.

- Osteopenia: A milder form of bone loss that can still predispose to VCFs.

- Other Bone-Weakening Conditions:

- Long-term corticosteroid use (e.g., for arthritis or autoimmune diseases).

- Rheumatoid arthritis, hyperthyroidism, or malabsorption disorders (e.g., celiac disease).

- Metastatic cancer or multiple myeloma weakening spinal bones.

- Minimal Stress: Everyday actions like bending, lifting light objects, or coughing can trigger fractures in osteoporotic vertebrae.

- Trauma: In some cases, minor falls or trauma can cause VCFs in already weakened bones.

Risk factors include age (over 65), female gender, low body weight, smoking, excessive alcohol use, prior fractures, or a family history of osteoporosis.

Symptoms of Vertebral Compression Fractures

VCFs can be subtle, with 50-70% being asymptomatic initially, per a 2020 study in The Lancet. When symptoms occur, they include:

- Sudden or Gradual Back Pain: Sharp or aching pain in the mid or lower back, often worsened by movement, standing, or sitting.

- Reduced Mobility: Difficulty bending, twisting, or walking due to pain.

- Height Loss: Loss of vertebral height from collapse, sometimes noticeable as a reduction in overall height.

- Kyphosis (Hunched Posture): A forward curve in the upper back, often called a “dowager’s hump,” from multiple VCFs.

- Tenderness: Pain when pressing on the affected vertebra.

- Radiating Pain: Discomfort may spread to the ribs or abdomen, though it rarely mimics sciatica (leg pain).

- Neurological Symptoms: Rare, but severe fractures may compress nerves, causing numbness, weakness, or, in extreme cases, bowel/bladder dysfunction (a medical emergency).

Symptoms may mimic other conditions like disc herniation or muscle strain, making accurate diagnosis critical.

Diagnosing Vertebral Compression Fractures

Diagnosing VCFs involves a combination of clinical evaluation and imaging to confirm the fracture and assess underlying bone health. The process includes:

1. Medical History

- Symptom Review: Discussing pain onset, location, triggers (e.g., movement vs. rest), and history of fractures or osteoporosis risk factors (e.g., menopause, steroid use).

- Risk Assessment: Using tools like the FRAX (Fracture Risk Assessment Tool) to estimate 10-year fracture risk based on age, gender, BMD, and other factors.

2. Physical Exam

- Evaluation: Checking for tenderness over the spine, height loss, kyphosis, or reduced mobility. Balance and gait tests assess fall risk.

- Neurological Assessment: Testing for numbness, weakness, or reflexes to rule out nerve compression.

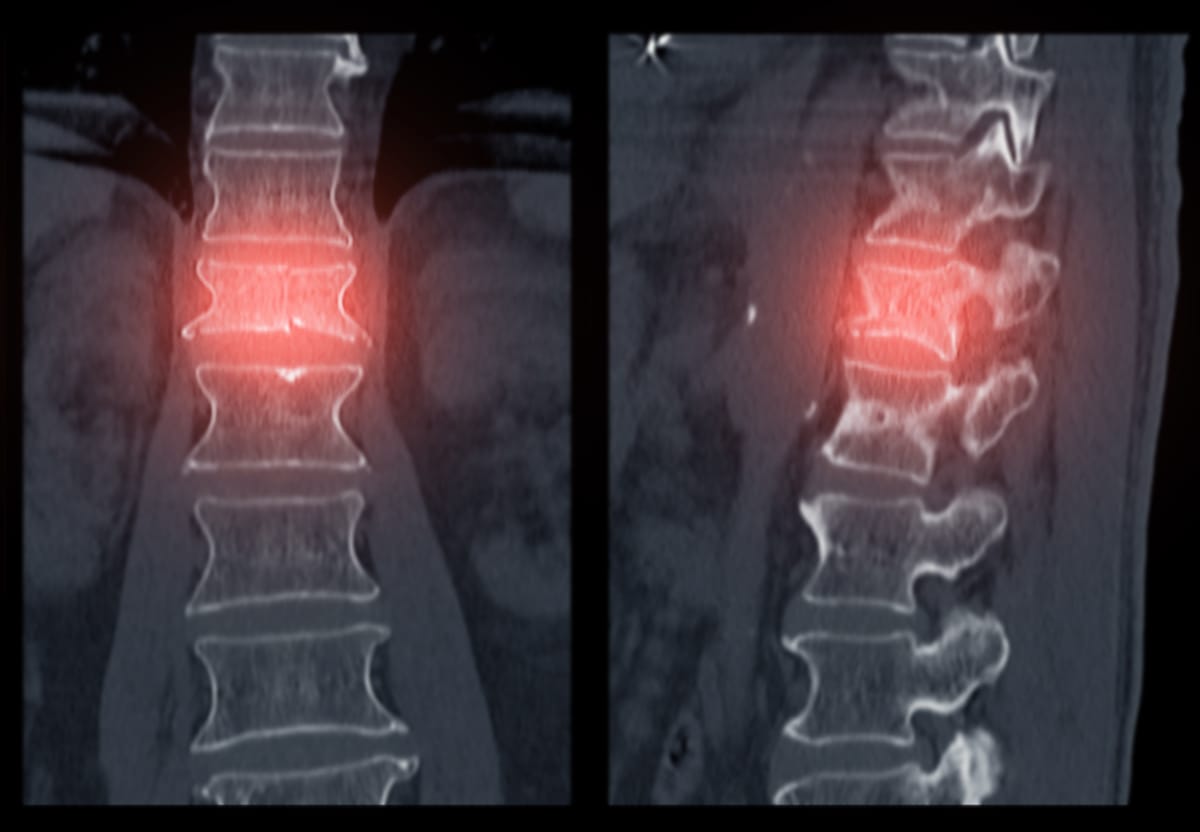

3. Imaging

- X-rays: The first-line test to detect vertebral collapse, deformities, or fractures. X-rays may show a wedge-shaped vertebra or reduced vertebral height. Sensitivity is 70-80%, per a 2021 study in Skeletal Radiology, but early fractures may be missed.

- MRI: The gold standard for visualizing acute VCFs, showing bone edema (swelling) or fracture lines with 95% accuracy. MRI also assesses nerve compression or other causes (e.g., cancer).

- CT Scan: Used if MRI is unavailable or to evaluate complex fractures, bone structure, or malignancy.

- Bone Scan: Detects increased bone activity in fractures, useful when MRI/CT is inconclusive or multiple fractures are suspected.

4. Bone Density Testing (DEXA Scan)

- Measures BMD in the spine, hip, or forearm to diagnose osteoporosis or osteopenia:

- Normal: T-score above -1.0.

- Osteopenia: T-score between -1.0 and -2.5.

- Osteoporosis: T-score -2.5 or lower.

- Severe Osteoporosis: T-score -2.5 or lower with fractures.

- Recommended for women over 65, men over 70, or younger adults with risk factors, per the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

5. Laboratory Tests

- Blood and urine tests rule out secondary causes of bone loss or fractures:

- Calcium and vitamin D levels.

- Thyroid or parathyroid function (e.g., hyperthyroidism).

- Bone turnover markers (e.g., C-telopeptide, osteocalcin).

- Tests for malignancy (e.g., multiple myeloma) or metabolic disorders.

6. Differential Diagnosis

- Ruling out other causes of back pain, such as disc herniation, spinal stenosis, sacroiliac dysfunction, or metastatic cancer.

A 2021 study in Osteoporosis International emphasized that combining MRI with DEXA scans improves diagnostic accuracy for VCFs and underlying osteoporosis.

Classification of Vertebral Compression Fractures

Classifying VCFs helps guide treatment by assessing severity, stability, and underlying causes. Common classification systems include:

1. By Morphology (Shape)

- Wedge Fractures: The most common, where the front of the vertebra collapses, creating a wedge shape. Often seen in osteoporosis, causing kyphosis.

- Crush Fractures: The entire vertebra collapses, leading to significant height loss.

- Biconcave Fractures: The middle of the vertebra collapses, creating a concave shape, often in the lumbar spine.

- Burst Fractures: Less common in osteoporosis, involving fragmentation of the vertebra, often from trauma.

2. By Severity (Genant Classification)

- Based on vertebral height loss seen on X-ray or MRI:

- Grade 1 (Mild): 20-25% height loss.

- Grade 2 (Moderate): 25-40% height loss.

- Grade 3 (Severe): Over 40% height loss.

- Severity correlates with pain, deformity, and treatment needs.

3. By Cause

- Osteoporotic: Due to low BMD, typically in older adults.

- Pathologic: Caused by malignancy (e.g., metastasis, multiple myeloma) weakening the vertebra.

- Traumatic: From high-impact injury, less common in osteoporosis.

4. By Stability

- Stable: No significant risk of further collapse or neurological damage.

- Unstable: Risk of progression, nerve compression, or spinal instability, often requiring surgical evaluation.

A 2020 study in The Spine Journal noted that wedge fractures are the most common in osteoporosis, with 60-70% classified as mild to moderate.

Treatment and Management Overview

While this post focuses on diagnosis and classification, treatment typically involves:

- Pain Relief: NSAIDs, acetaminophen, or short-term opioids; bracing for support.

- Interventional Procedures: Vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty (injecting bone cement) for painful, stable fractures, with 70-80% pain relief, per a 2020 study in Pain Physician.

- Osteoporosis Treatment: Bisphosphonates, parathyroid analogues (e.g., teriparatide), or denosumab to improve BMD and prevent further fractures.

- Physical Therapy: Gentle exercises to restore mobility and prevent falls.

- Lifestyle Changes: Calcium (1,000-1,200 mg daily), vitamin D (800-1,000 IU daily), weight-bearing exercise, and smoking cessation.

Living with Vertebral Compression Fractures

VCFs can cause chronic pain, height loss, or mobility issues, impacting daily life. Keep a record of pain, mobility changes, or falls, and share details with your healthcare team. Support groups, through organizations like the National Osteoporosis Foundation (nof.org) or online platforms like Reddit, offer a space to connect with others and share coping strategies.

Emotional support is vital, as pain and fear of fractures can lead to anxiety or reduced activity. Lean on counselors, family, or friends for encouragement. Practical steps, like using a back brace, installing grab bars, or practicing balance exercises, can reduce fracture risk and improve confidence.

Why Awareness Matters

VCFs affect millions, with osteoporosis causing 700,000 spinal fractures annually in the U.S., yet many remain undiagnosed due to their silent nature, per a 2020 review in Osteoporosis International. Raising awareness about VCF diagnosis and classification ensures timely intervention, reducing pain and preventing further fractures.

If you’re experiencing unexplained back pain, height loss, or have osteoporosis risk factors, consult a primary care doctor, spine specialist or international radiologist about screening. Resources like the National Osteoporosis Foundation (nof.org) or the International Osteoporosis Foundation (iofbonehealth.org) offer valuable information and support.

By understanding vertebral compression fractures, we can empower individuals to protect their spine and maintain mobility. Let’s keep the conversation going—no one should face this pain alone.

Disclaimer: This blog post is for informational purposes only and not a substitute for professional medical advice. Consult a healthcare provider for diagnosis and treatment of vertebral compression fractures or osteoporosis.